Today, we often take antibiotics for granted. Since the discovery of penicillin in 1928, these powerful medications have become a cornerstone of modern medicine. Physicians regularly prescribe them to combat a wide variety of bacterial and fungal infections. However, in recent years, many antibiotics have become increasingly ineffective. Even as researchers work to produce new and more-powerful medications, the pathogens are rapidly developing resistance to them, creating an endless game of bacterial “Whack-A-Mole”.

Antibiotic resistance is the result of a process that occurs frequently in nature: bacterial transformation. Bacteria reproduce asexually; they create exact copies of themselves by dividing in half repeatedly. This reproductive strategy is effective at producing many offspring very quickly, but the lack of genetic diversity also has drawbacks. To acquire some variation in their genome, bacteria regularly exchange segments of their DNA with other bacteria of the same species, or acquire it from dead cells. The bacteria can pass the new genes on to their offspring when they divide, and if they prove advantageous, these genes will become increasingly common in the population over time. Humans have long exploited the process of bacterial transformation in order to use bacteria to produce therapeutic proteins, such as insulin (the same process we use in ABE to make red fluorescent protein).

Bacteria initially acquire resistance via random mutation, but they subsequently pass these advantageous changes on to their offspring, and spread them to still more pathogens via transformation. The “superbugs” are believed to have originated from a few bacteria whose genetic code rendered them immune simply by chance. While an antibiotic may have wiped out the vast majority of the bacteria, the few that survived reproduced and passed on their immunity. Many patients inadvertently contribute to this problem when they cease taking their medications as soon as they begin to feel better, without finishing the prescribed course of antibiotics. When taking antibiotics, it is essential to finish all the medication to ensure that all of the dangerous bacteria are eliminated and are not able to continue reproducing.

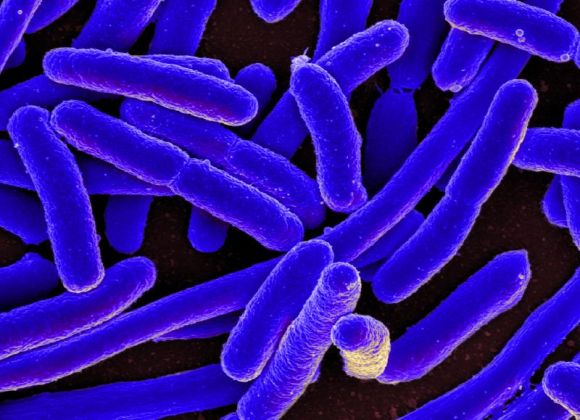

While some resistant bacteria are relatively benign, a number of these “superbugs” can be life-threatening to humans. A few of the most dangerous ones include strains of tuberculosis, pneumonia and gonorrhea bacteria, as well as Enterobacteria (a group of pathogens that can cause deadly gastrointestinal infections such as Salmonella and E. coli) that have become resistant to multiple antibiotics. Once a patient has acquired a resistant infection, doctors are often powerless to stop it, even with the most powerful antibiotics available. Pneumonia, for instance, is quite common and is the leading cause of infectious-disease-related death in elderly Americans. One recent study showed that over 1 in 4 pneumonia patients did not respond to the first course of antibiotics administered.

Resistant infections are rapidly becoming a worldwide public health crisis, and it is essential that we combat them immediately and remain vigilant. Preventing the overuse of antibiotics and curbing the transmission of disease, particularly in hospital settings where these bugs are more common, will be essential steps in this ongoing bacterial arms race.

For More on Drug Resistant Bacteria: