Since October, Australia has been facing widespread and devastating fires. While the severity and extent of the fires are unprecedented, environmental degradation is not new to the country, with droughts and fires common in many rural communities. Teenagers in these farming regions often feel the brunt of this, says Eugenia O’Brien of the University of Sydney, who coordinates the ABE Australia program. “Why bother with school when the entire family enterprise is in tatters?”

Their struggles touch on one of the many unique challenges facing the education community in Australia as it works to bring equity to all schools and students. “Equity is not equality, but recognizing differences and adjusting programs or resources accordingly,” O’Brien explains. “Equity is about ‘fairness,’ and fairness can mean different things across the diverse and variable education system.”

Indeed, Sophia Mansori, the evaluation director in the ABE Program office, says that supporting equity in a global context often starts with understanding that “‘disadvantaged’ looks and means incredibly different things from country to country.” Once those distinguishing characteristics are identified, it becomes much easier to assign resources to make experiences equitable.

To help better understand the equity landscape, ABE has been systematically surveying its sites globally. “Challenges shared by ABE sites via the survey include teacher preparation and background, lack of resources and support at the school, school location and access to ABE, and assumptions about student needs and abilities,” Mansori says. To overcome these challenges, sites are taking a number of different strategies that speak to their unique regional needs.

In Australia, the gap between communities can be vast, literally, with enormous distances between towns, especially in rural New South Wales (NSW). Additionally, the gap between students socioeconomically can be vast. A story in the Guardian cited a recent study that poorer students in Australia are 18 months behind their better-off peers at school, and regional students were on average eight months behind at school. “One of the largest factors in school performance was the quality of teaching staff, but the school governance, the classroom environment and resources were also major factors,” the report said. “We are beginning to highlight the problems, but the solutions are few and far between,” says O’Brien.

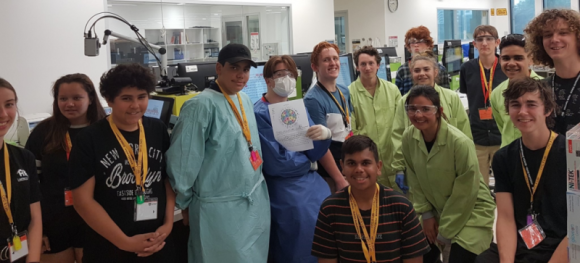

“We think the ABE can help to alleviate some of the challenges facing under-resourced NSW schools, even if it is just for a couple of weeks each year,” she says. “Providing resources that are beyond the means of many schools and building capacity and confidence in teachers—while transforming the classroom environment to one of high expectations, rich learning, and practical applications—are all part of the mix.”

The ABE program in Australia has received a grant from the University of Sydney’s Widening Participation and Outreach team that aims to increase the participation of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander students and their teachers in STEM activities and professions. The grant enables them to purchase an ABE kit for the exclusive use of up to 12 schools and to cover training costs. “These are schools that have a low socioeconomic base, have a high proportion of Indigenous students, or are geographically isolated,” O’Brien says.

Getting schools onboard has been more difficult than anticipated, she says. “We learnt very quickly that providing a free program is not always enough. Some schools need additional support, time, and resources to be able to participate. Even basic science lab resources can be lacking in some of the schools we work with—some schools have indicated that they do not have conical flasks to be able to make agar gels so we have included some flasks in the kit. Others have too much to deal with at school to take on an additional endeavour. Some do not have the support of their executive. Some teachers worry about the behaviour of their students and were concerned the equipment would be damaged.”

Such challenges speak to the broader challenge of providing equity in a global STEM education context. ABE has a leg up among other programs, O’Brien says, as it provides preparation and resources that go beyond just the equipment.

“Even though delivering the ABE program takes a lot of preparation and effort for teachers, it is prescribed and ready made to pick up and run with,” she says. “We really hope that we will be able to provide tailored and appropriate assistance and support for whatever is needed to deliver the program in underprivileged schools in the coming years. We want to understand what the challenges are for individual schools and plan for how we can help teachers make the most of the equipment and resources.”

Despite the challenges, success stories abound from Australia. “The passion, dedication, and drive of the teachers is what overcomes adversity,” O’Brien says. For example, science teacher Brian Edmonds regularly drives 660 kilometers (410 mile)—or 8 hours—to Sydney just to get a scientific kit that will enable his students at Tenterfield High School to participate in cutting-edge labs. Tenterfield is a small regional high school in far north, rural NSW. For him, it’s a labor of love: “Teaching young people about science and its real-world applications is very important,” he says, “and this program allows schools who can’t afford to get to Sydney to get the equipment, or do not have biotech training, to enrich their students and give them a greater understanding of science.”

“Having under-resourced schools as part of our ABE community enriches the whole and provides perspectives and experiences that are so important to share across different schools,” O’Brien says. “We hope that the community of participating schools will build into a supportive and communicative network.”