Since 1996, elementary school teacher Kristen Toth has been participating in “Draw a Scientist” exercises with her science students. Over those nearly 30 years, Toth has seen tremendous change, especially in how the students’ identities are reflected in their drawings. The biggest change has been in gender; whereas none of her students in 1996 drew a female scientist, now, about 60% did. Although only one data point, her students reflect broader trends for women in science over the past several decades, wherein women are more represented in STEM fields. Work remains, however, to broaden how we view scientists and the opportunities everyone has for advancement.

The “Draw a Scientist” exercises—a simple and effective way to make representation and stereotypes engaging for students—started as a tool for social scientists to understand changes to perceptions of scientists over time. The researchers would simply ask children at varying ages to draw a scientist and then identify various characteristics in the drawings, such as gender, race/ethnicity, clothing, and equipment. In analyzing these features over the past 5 decades, researchers have been able to indirectly measure stereotypes of scientists.

Credit: A. Muñoz, 2024

The images often include Einstein-like “mad scientists” with crazy hair, as well as traditional symbols of chemistry, like lab coats and flasks. But there are also signs of change, especially when it comes to gender.

When the studies first started in the 1960s and 1970s, less than 1% of school children drew a female scientist. In a 2018 study, researchers found that number had jumped to more than 30%. That gender data also varied based on the ages of the children asked to draw a scientist, with kindergartners drawing roughly equal proportions of female and male scientists and with the children more likely to draw someone with their own gender. By high school, however, students were drawing more male scientists than female scientists by a ratio of about three-to-one, suggesting that the gender-based stereotypes form over the course of someone’s childhood.

In Toth’s classes in Northern Virginia, the change has also been significant. In her current 5th-grade class, not only are all students drawing more female scientists, they are also increasingly drawing scientists who match their own identities. She also noticed in the drawings more female scientists in lab coats. “I wonder to myself if that could be a direct impact of COVID, and this group living through watching health care workers, scientists, and even some teachers wearing full gear as they researched desperately for vaccines and a cure,” she says.

The change in gender representation has been transformative: “In comparison to when I began doing this study in the nineties, and then have continued every year since, the trend I most celebrate is the increase in the number of girls who immediately see women as scientists from the moment they put their pencils to the paper,” she says. “I’m also proud to see any boys, let alone boys in the double digits, see women in the role of scientists. When I began this study, none of my students, male or female, did that for several years.”

That children are increasingly able to see more people who look like them as scientists is a testament to the broadening views society has about who can be and should be a scientist. Books, films, and TV shows that feature scientists with varying backgrounds all help show young people that they too can pursue science; media representation can be especially important for students and communities that have less exposure to real-world scientists.

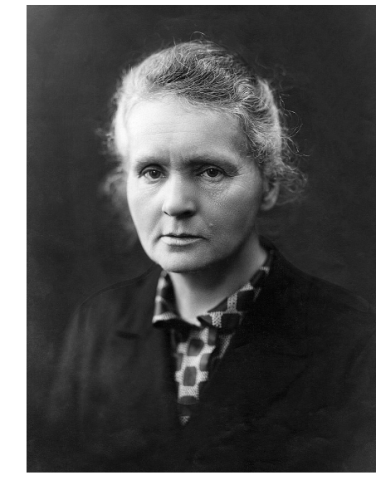

Stories that show scientists’ successes and struggles must be part of those efforts. Think about Marie Curie, a female scientist frequently recognized in society. As important to knowing her contributions to science might be her story: her pursuit of science as an immigrant, traveling from Poland to France to attend university, against a backdrop of rampant sexism in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

Stories that show scientists’ successes and struggles must be part of those efforts. Think about Marie Curie, a female scientist frequently recognized in society. As important to knowing her contributions to science might be her story: her pursuit of science as an immigrant, traveling from Poland to France to attend university, against a backdrop of rampant sexism in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

When we think of scientists as singular geniuses or separated from their socioeconomic setting, we may unknowingly be putting a wedge between daily life and the scientific process. The more we can bridge that gap with students—showing them the human stories of scientists, whether current, historical, or fictional accounts—the broader the reach of science can become.

Our pictures and stories of scientists matter. Alongside hands-on science activities, whether Science Olympiad, science fairs, or programs like ABE, these efforts will continue to shape women’s history in the decades to come.

Lisa M. P. Muñoz is the author of Women in Science Now: Stories and Strategies for Achieving Equity (Columbia University Press, 2023) and is a communications consultant for ABE.