While many professors are actively discouraging their students from using AI, others are embracing the technology as a new way to enhance productivity and generate novel ideas. Since ChatGPT became available to the public, physiology professor Naava Schottenstein has been leveraging it in the classroom, from daily activities like writing emails to helping to create variations of tests and building out curricula. As site director for ABE Central Ohio, Schottenstein is also testing whether generative AI can help develop new labs for the ABE program.

“ChatGPT has made me 1,000 times more productive,” she says. “I could not see going back now. I can give you a stack of things that it has helped me create—active learning exercises for my class, study guides for my classes, PowerPoint presentations, new exam questions. … I can do things so much faster.”

For Schottenstein, by using the AI-based technology for more mundane tasks, she has more time to thoughtfully engage with her students and the curriculum. The generative AI tools also are helping her to approach problems in new ways.

At a recent meeting of new ABE site directors, Schottenstein and others were discussing the need to “beef up their culturally responsive pedagogy,” Schottenstein recalls. After that meeting, her thoughts turned to ChatGPT and whether it could help her come up with some ideas to fill the need in that space.

Schottenstein’s prompt to the AI was: “Give an example of a culturally responsive curriculum for the Amgen Biotech Experience.” While the prompt was simple, she had previously “trained” it with information about the ABE program, including about its labs and how they are run and overall objectives. What resulted was an outline of a five-lesson module entitled Exploring Genetic Diversity in Our Communities.

The AI-generated module is essentially an extension activity that builds off a DNA extraction lab. Commonly such extension labs will teach students how to extract DNA from a fruit like a strawberry or banana. In the new module, the AI suggests using produce from the students’ respective cultural backgrounds, whether that is a persimmon or a plantain.

Recognizing the diverse backgrounds of ABE students is an important focus for the program and one that especially hits home for Schottenstein in central Ohio. The local schools reflect broad racial, ethnic, religious, and economic diversity, and so connecting the ABE lessons to individual backgrounds strengthens the connections the students can make between science and society.

While the ChatGPT came up with the outline for the module, Schottenstein needed to make some modifications to ensure the lessons would be practical in a classroom setting. Thinking through the AI outputs and using the new ideas alongside her own expertise, rather than just taking what it generates at face value, is an important part of working in the new digital AI world.

This is true for various aspects of Schottenstein’s work with AI technology. She has also used generative AI to help create more culturally responsive images in presentations to her students at Columbus State Community College.

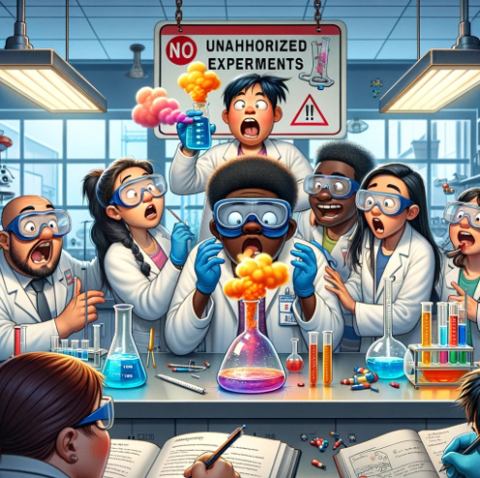

In the past, she had to rely on stock photos of scientists that were often devoid of diverse representations. Now she prompts AI programs to create more representative images. “Being able to have pictures that show Muslim students, Black students, Hispanic students, females, etc., in the lab is so important for students,” she says. “It's easy for me to go on the internet and find a white male scientist with a pipette in his hand and post that in a presentation; it's not as easy to find a group of very diverse looking people in a lab space.”

Getting AI-generated images is not without its own difficulties, however. It will often take several iterations of prompts for Schottenstein to get usable photos and even then, things may look off. Misspelled words, extra fingers, an anthrax mask instead of a lab mask, to name a few—she and her students have fun poking fun at the images. Yet Schottenstein still prefers them to the less-diverse stock photos. “You want to show pictures to your students that reflect themselves, so they can see themselves in science,” she says.

Left to right: Drew Spacht (ABE Central Ohio Site Coordinator and Lab Technician), Matthew Saelzler (ABE Subject Matter Expert), and Naava Schottenstein (ABE Central Ohio Site Director)

Schottenstein is hopeful that the AI technology will continue to help her not only with her work as a professor but also with her work for ABE Central Ohio. Only 2 years old, the site is engaging in new types of outreach, such as through cool timelapse videos on social media and working with various boys and girls clubs in their local community this summer.

The possibilities for AI in education are vast, Schottenstein says. And while she understands the hesitation among some, she encourages an open mind. As one example, she points to students using ChatGPT to write emails. Although the emails could get impersonal or feel off, she sees it as a first step to helping students to organize their thoughts in a first draft. And she sees real value there in helping, for example, students for whom English is not their first language.

“The more I use it to help me draft an email, the more I learn how to write a good email or how to write a good letter,” she says. “Yes, it's doing some of the work for me, it's helping me to create something, but at the same time, I'm learning from it.”