In an era where a virus has upended our lives and harmed many, it’s easy to forget that viruses can also be a force for good. Researchers have recently been experimenting with harnessing several virus’s natural characteristics to treat conditions such as sickle cell disease.

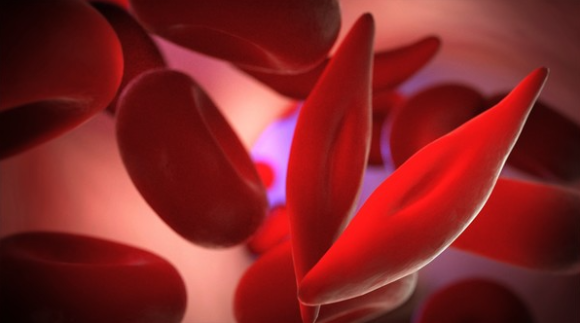

Sickle cell disease (SCD) is an inherited genetic condition in which the red blood cells have an unusual shape. Rather than being round discs, in SCD-affected individuals, the red blood cells are sliver-shaped, making them prone to clumping. Living with SCD can be extremely painful, and it puts patients at greatly increased risk of stroke, heart attacks, infections, and organ failure.

Researchers have long sought to cure SCD patients but have previously met with limited success. The only known long-term cure for SCD is a bone marrow transplant. The new marrow will produce unaffected red blood cells, but the transplant itself can also cause severe health complications. Gene therapy, which replaces an affected gene with an unaffected version, is considered to be the next frontier in the battle against SCD. Researchers have identified a tiny mutation in the beta-globin gene, which is involved in hemoglobin production, as the main gene responsible for producing sickle-shaped cells.

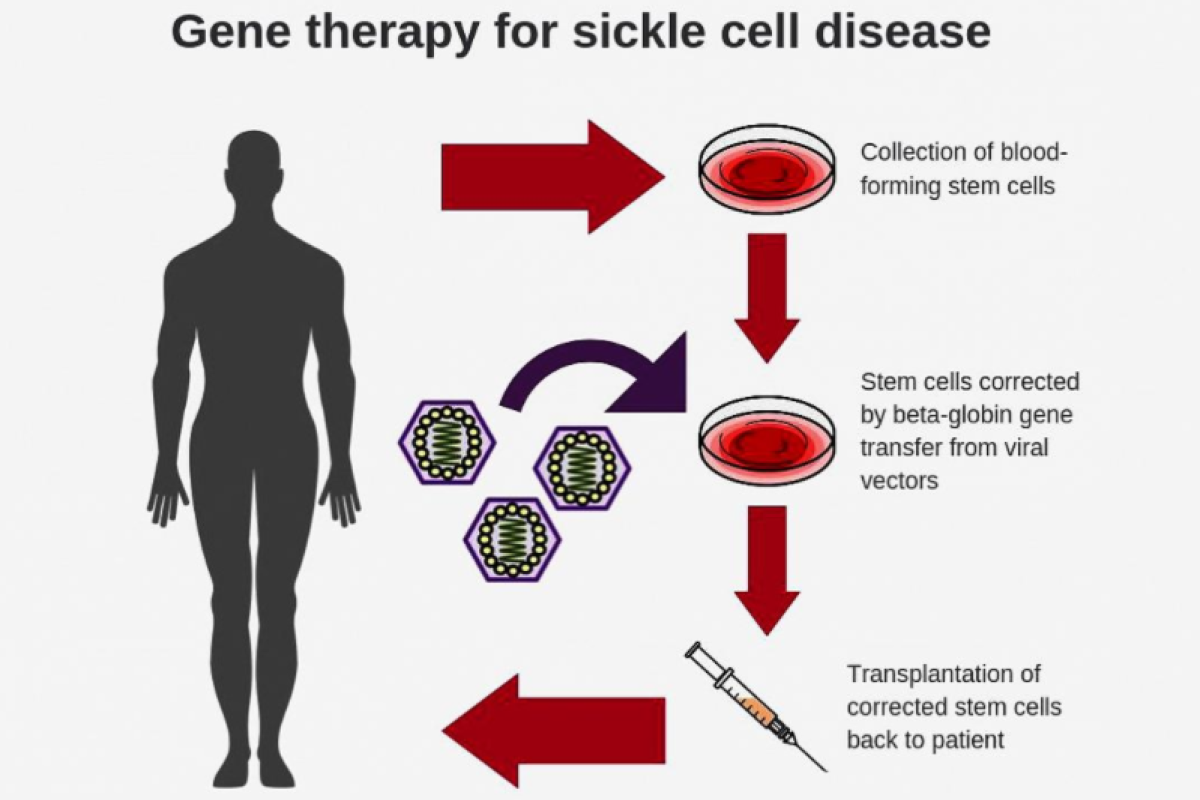

In late 2019, researchers at the U.S. National Institute of Health announced that they have harnessed a new vector for introducing a new gene; a virus. After removing some of the patient’s bone marrow cells, the virus can deliver a “payload” of normal beta-globin genes, which replace the affected section in the cells’ DNA. The retrofitted bone marrow cells are then reintroduced to the patient, where they can produce healthy red blood cells. Because the bone marrow cells are the patient’s own cells, rather than coming from a donor, it eliminates many of the risks of a traditional bone marrow transplant.

Diagram shows steps involved in conducting gene therapy for sickle cell disease. National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute

This strategy has shown promise in several animal models and may soon be ready for human trials.