Tattoos are a form of body modification where ink is inserted into the skin to create words and art. Tattoos have long been a form of self- and cultural expression. They have been found on mummified skin dating as far back as 3,000 BCE and are represented in ancient art from as far back as 4,900 BCE. While many people tattoo themselves to show individuality and creativity, in some cultures tattoos reflect social and political rank, power, and prestige or honor the history of a culture like the tattoos of the Māori. The skills used to create tattoos have, in some traditions, been passed from parent to child (often father to son) for generations.

Humans have been creating tattoos far longer than they have understood the body’s reaction to them. Even today, we rarely think of what is taking place “just below the surface” when receiving a tattoo and the different body systems involved. How do tattoos stay in place if the body’s cells are constantly dying and being replaced? Why are they so difficult to remove? Let’s take a look.

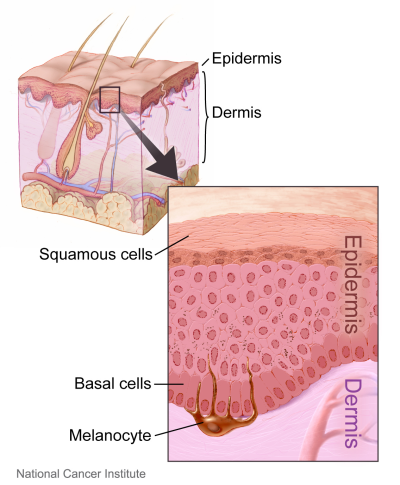

When you get a tattoo, the ink is inserted via needle into the dermis (the second layer of skin). Your body sees this ink as a foreign invader, and activates the immune system to seek out and destroy the unfamiliar material. As part of this process, special white blood cells called macrophages envelop the ink and try to break it down with enzymes to a size small enough to be disposed of through the body’s lymphatic system. (When the tattoo needle introduces bacteria at the same time as introducing ink, a similar macrophage response takes place. If the bacteria multiply faster than the white blood cells can destroy them, you will get an infection). However, large tattoo ink droplets are not broken down by these enzymes. Once taken in by a macrophage, the ink molecules are stuck there. It is this trapped ink that you see when admiring your or your friend’s latest tattoo.

But like nearly all cells within the human body, macrophages don’t live forever. Scientists have found that when a macrophage dies (white blood cells last for a few days to just over a week), the ink is once again released into the dermis. But almost immediately, a fresh new macrophage arrives to destroy the freed ink, and once again, the ink is trapped. And this process continues over time, which keeps the tattoo in place. That said, some smaller droplets of ink over time become small enough that a macrophage is ultimately able to remove them through the body’s lymph system, making tattoos fade slightly as the years pass.

Now, what if you have the name of your loved one tattooed on your arm but the relationship has soured? What can be done to get rid of the tattoo? Because of the macrophage death/renewal process, removing tattoos can be difficult. Lasers are used to break up the ink droplets into small enough sizes that the body can successfully remove. This process often takes multiple costly visits with the service technician. However, scientists’ knowledge of the way that macrophages preserve tattoos may help in their eventual removal. If we can somehow stop the arrival of new macrophages to the area where a tattoo is being removed, it could speed along the laser process and allow the lymphatic system to more easily drain the fragmented particles. But there is still much research to be done before we can make this a reality.

One question that arises when thinking about the body’s reaction to a tattoo is: If someone is immunocompromised, is it safe to get a tattoo? The jury is still out. There have been instances of immunosuppressed people having severe muscle pain and swelling after receiving a tattoo. But it is not clear if these instances were caused by the tattoo process or by something else (e.g., an injury) that coincided with getting the tattoo. It seems plausible that a body already struggling to fight infections could be overwhelmed when a tattoo is added to the equation. But until more research is completed and shared, we can’t be sure.

Other research has shown a possible link between tattoos and a strengthened immune system. As noted above, when you get a tattoo, the body’s immune system immediately bolsters itself to fight off infection, but research has found that this happens not just at the “injured” tattoo site but throughout the entire body, and the response has shown to be cumulative. In addition, as part of the body’s endocrine system, levels of cortisol (the hormone known to produce the “fight or flight” response in times of stress) seem to decrease during subsequent tattoo creations. When cortisol levels are too high over a period of time, blood pressure and the processing of food can run amok, causing diabetes, and anxiety can become uncontrollable. These decreased moments of cortisol post-tattooing can, thus, be beneficial to overall health.

So, while tattoos seem only “skin deep,” research continues to show us that they affect numerous body systems, including the immune, lymphatic, and endocrine systems. Remember this the next time you pass a tattoo parlor or admire someone’s ink.

To learn more about the human immune system and how it is used, check out the following resources:

• Khan Academy Inflammatory Response Video

• LabXchange The Immune System Pathway