“Everyone needs science and science needs everyone.” That mantra from the Amgen Foundation leads our efforts here at the Amgen Biotech Experience (ABE) Program Office to bring hands-on science to diverse populations globally, with several efforts focused on underrepresented and underresourced communities. Alongside those efforts, we love highlighting the stories of our teachers and scientists from various backgrounds around the world through the work of the program’s longtime science writer, Lisa M. P. Munoz.

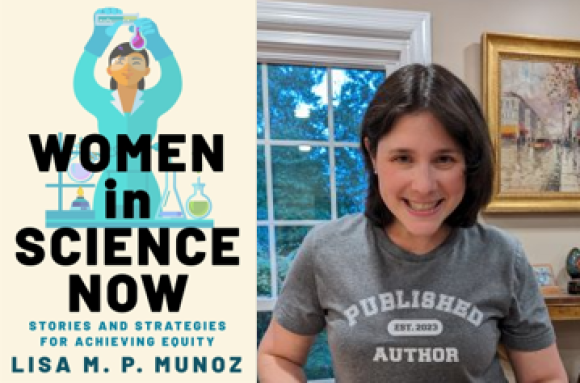

Whether writing articles for ABE about career paths or creating videos that showcase the impact of Amgen Scholars, Munoz tells stories about scientists to help inspire and empower the next generation of innovators, and she has a new book out this month, Women in Science Now: Stories and Strategies for Achieving Equity. Pairing stories of scientists with social science data, the book examines the continued and persistent gender gap in STEM fields, offering new perspectives on how to make those fields more equitable for everyone.

We sat down with Munoz to learn a bit about her book, why she wrote it, and the importance of representation and equity across the scientific enterprise.

Why did you write Women in Science Now?

I wrote the book to learn how scientific organizations and workplaces can create inclusive and welcoming environments that retain women scientists. Over the course of my 20+ year career in science communications, I have interviewed hundreds of different scientists about their work across biotechnology, immunology, geoscience, psychology, neuroscience, among other disciplines, and I have heard time and time again about the unique struggles facing women in science. Within those stories were echoes of my own early struggles in engineering during my undergraduate years. After an editor at Columbia University Press approached me to write a book while I was doing publicity work for the Emmy-award-winning documentary film Picture a Scientist, my thoughts instantly fell to all those stories. In that moment, I knew I wanted to write a book that would bring a social science perspective to the thorny problem of discrimination in the sciences: How can we use science to make the sciences more equitable?

What is the primary problem facing women in science?

While many undergraduate science departments begin with roughly equal numbers of male-identifying and female-identifying students, the numbers shift in favor of the male-identifying students at each phase of the educational path, from bachelor’s degrees to master’s, then master’s to PhDs and postdocs, and through to employment. Some people refer to that as the “leaky pipeline,” though I prefer to think of it differently. To quote from the book: “Women are not dripping through holes in the system; they are being pushed out of a system that historically did not want them in the first place, even if it wants them now.” Active forces are pushing women out of science at different points in their careers and making it challenging for those who stay to advance and thrive.

You mentioned early struggles you had in undergraduate school. Can you elaborate?

I was an undergraduate student at the College of Engineering at Cornell University. I chose engineering because I loved the idea of creatively solving problems using science. I also wanted to choose a very practical career that would lead to financial stability, and I was heavily inspired by my older sister who was pursuing engineering. When I arrived at Cornell. I had no worries about fitting in or whether I could “cut it.” But as I progressed through my required engineering courses, despite being at the top of my class in high school, including taking advanced math and science classes, I struggled. It felt as though I was actively being weeded out of the program, and support was not easy to find, especially from peers.

So, what did you do?

I made it through those engineering courses and did alright, but decided that I did not want to be an engineer after all. I was fortunate to be able to stay within the engineering college by pivoting to an interdisciplinary earth science program. Within that program, I heard a transformative guest lecture from an on-air meteorologist at CNN, Valerie Voss. After the lecture, I went right up to Ms. Voss and asked her if I could intern at CNN and would become their first (to my knowledge) meteorology/science intern that next summer. Although I decided that TV was not for me, I decided to take as many science writing and journalism classes as I could in my last 2 years at Cornell. The day after I graduated, I started a job producing short-format radio programs on nature and the environment, and I have not looked back since. I’ve had a fulfilling career in science communications, working as a magazine reporter and managing editor, press officer, consultant, and now, author.

If you could go back, would you do it any differently?

No, I would not do anything differently, but I would want my college self to worry less and to know that I would find my path.

Why do you think representation is so important in the sciences?

Representation is massively important, as it can show someone a path they might not have ever considered before by seeing someone else succeed. That’s a big part of what drives my work for ABE in highlighting the paths of different scientists. Had I not interacted early in life with women in science, I might not have pursued a STEM field, as my parents were not scientists, and it was not a topic that was stressed in my elementary school. In addition to my sister Robyn, who was studying engineering, being a huge influence, I had some amazing science teachers.

Tell us more about your high school science teachers.

One example is my AP chemistry teacher, Barbara Broadway; she showed me science in a way I had never seen before. She ran an afterschool water quality club, where she would take students out to a local creek in Atlanta, GA, to sample water, and we’d then test it for various contaminants in the lab. It was my first exposure to fieldwork, trudging out in wading boots, getting muddy, and loving the feeling of contributing data to my community. On top of that, I was able to participate in international scientific research through an exchange program with students in Russia. Students from Russia came to Atlanta to live with us and test water in our creek, and I traveled to Rostov-on-Don in southwestern Russia with Mrs. Broadway and peers to test water on the Don River for 4 weeks. As a 16-year-old, I got to do collaborative global research! Mrs. Broadway passed away a couple of years ago, and I think of her often and the tremendous influence she had on my path.

Munoz during her high school water quality club's Eco-bridge exchange program

Do you have any role models now?

So many scientists inspire me today, including the amazing women whose stories are featured in my book. Not only do they all contribute significantly to their respective fields, but they also are all fantastic mentors and role models, working toward making their fields more equitable for everyone. One quick example is Janet Antwi, an organic chemist who is featured in my book and whom I wrote about for Amgen Scholars. Her work in teaching and mentoring undergraduates in the lab is truly inspirational. I met her at a recent Amgen Scholars symposium, and just seeing how she interacted with undergraduate researchers in biotechnology motivated me toward more mentorship in science communications.

What do you hope people take away from Women in Science Now?

We must close the gender gap in science to fix the scientific enterprise. The good news is that we have a large body of research from scientists themselves to guide us in closing that gap. I love the idea that we can use science to help fix science, and I found it inspiring to talk to some of the people working to make that happen. I hope readers will as well and that it will motivate individuals and institutions to think more deeply about how they can effect change.