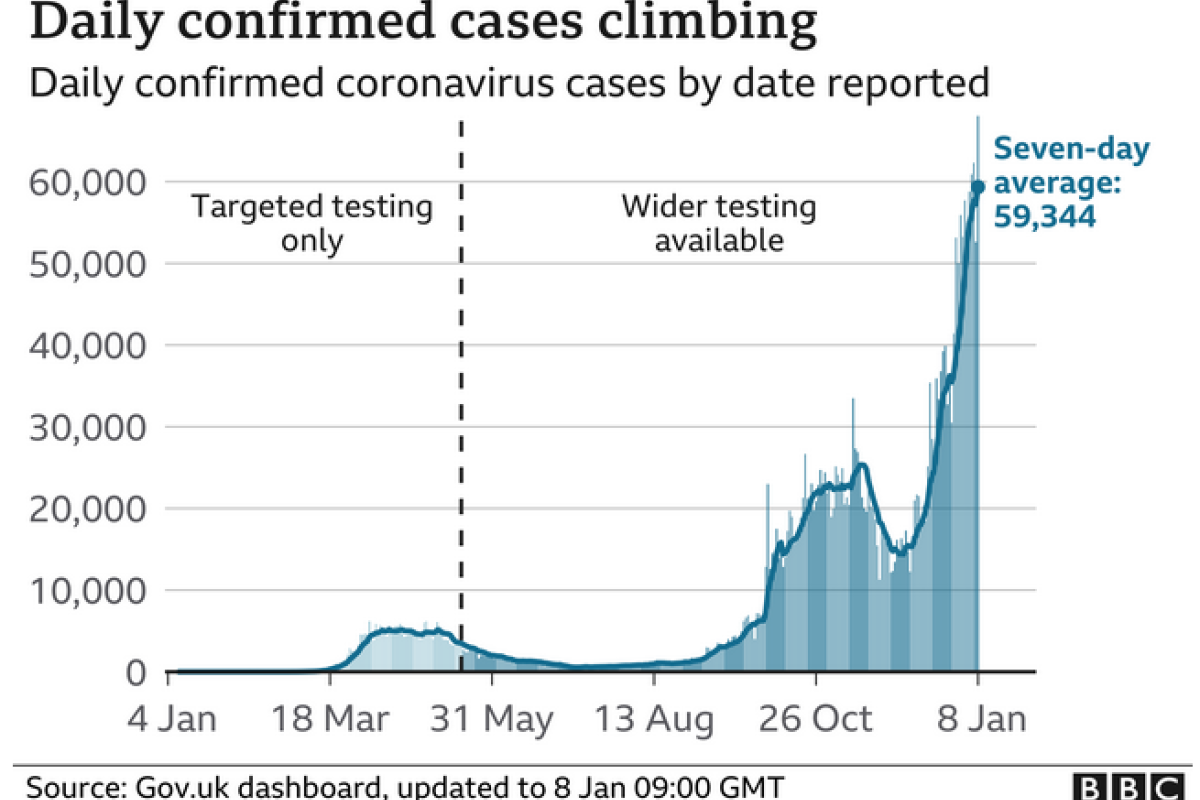

In recent news, there has been a lot of talk about a SARS-CoV-2 (the virus that causes COVID-19) variant that seems to be more contagious than previous strains. In fact, the UK recently went into another lockdown in hopes of preventing further transmission as rates there are now at an all-time high, as shown in the graph below, published by the BBC.

But what IS a variant of a virus? And, why is the UK variant any different from the mutations of SARS-CoV-2 that exist? Well, to begin to understand virus variants, we need to start at the very beginning. A variant is simply a virus that has undergone a mutation to its DNA or RNA (SARS-CoV-2 is an RNA virus). Many viruses mutate regularly (though some are remarkably stable like the virus that causes measles). This is actually a normal evolutionary function of viruses, simply the product of a natural process in which viruses develop and adapt to their hosts as they continue to replicate. Scientists think that there are over 40,000 variants of SARS-CoV-2 already!

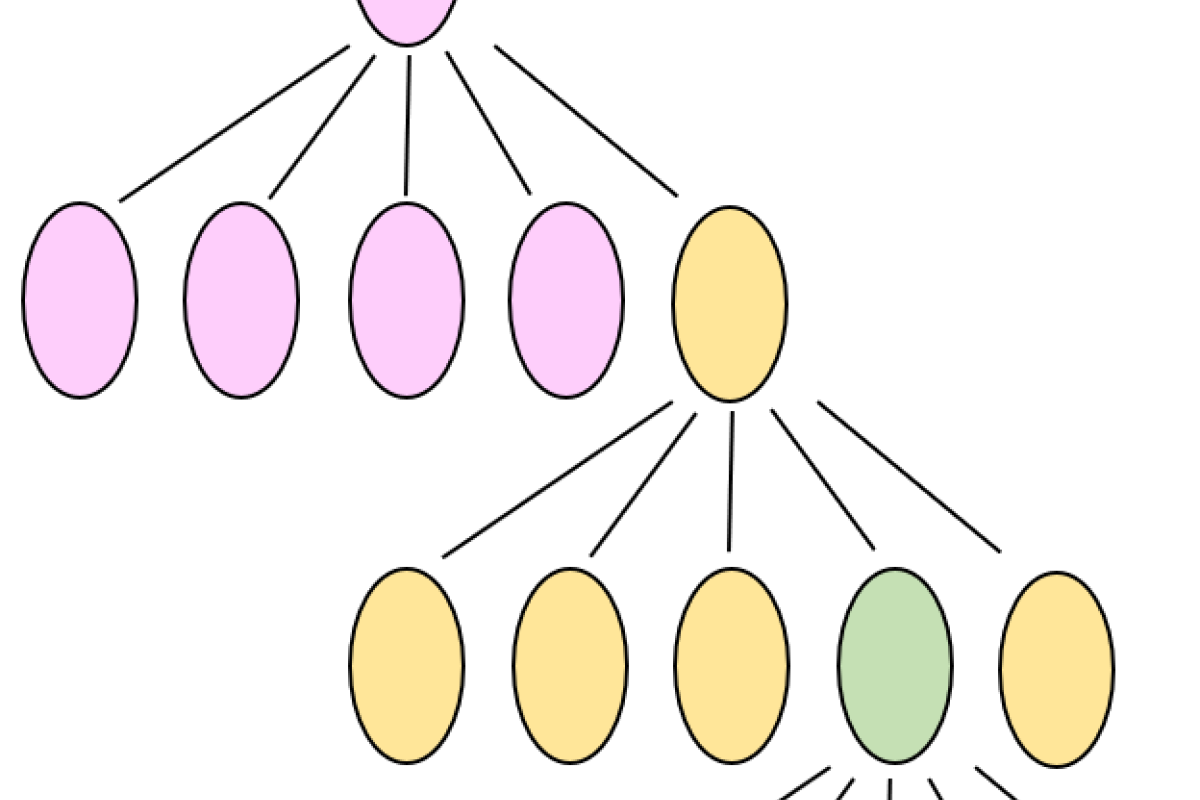

Here is a visual representation of what this would look like (a differently colored circle represents a mutation or a variant):

Viruses, unlike many other species, are able to evolve rapidly over short periods of time because they reproduce very quickly. RNA viruses often mutate more quickly because their genetic material (RNA) doesn’t undergo “quality assurance” like DNA does when it replicates. A good analogy for understanding a variant is to think about it as a change that is made to a book and then that book becomes replicated with that change, and the changes and replications continue on and on. The whole book doesn’t change, but instead, pieces of the book change in each new version produced.

Normally, variants are not a cause for concern. In fact, SARS-CoV-2 seems to be acquiring about one new mutation in its genome every 2 weeks, but many of the mutations are shown to be silent (i.e., do not change the structure of the proteins). So, using our book analogy, this would mean a copy of a book would be published, and every 2 weeks a new word may be added to a certain chapter. In all, the new word wouldn’t necessarily change the content of the book, but when this is done repeatedly over the course of months, some changes cause disruptions to understanding. In the case of this problematic variant, this variant (now named B.1.1.7 ) is shown to change the ability of the virus to become more resistant and increase its transmissibility. In fact, experts now think that the new variant is 50%–74% more transmissible than other previous dominant strains, and scientists are estimating that it could be responsible for up to 90% of all new COVID-19 cases in England by mid-January. This means, within a timeframe of 3 months, this variant will compromise over 90% of the cases reported. And, by March, scientists believe that this variant will be the primary source of all COVID-19 infections within the U.S. as well, as reported by the New York Times.

There is some positive news, however. Experts believe that the newly developed vaccines, now being administered to people worldwide, will still work against the novel variant. That is because when vaccines are developed, they are designed to stimulate the immune system to recognize a certain protein that makes up the virus and destroy it. It is through this mechanism that your body will establish an immune response, and although you are exposed to just a fraction of that protein in the vaccine, it is likely enough for your body to recognize if SARS-CoV-2 were to invade your immune system. According to the CDC, 99% of the proteins in the UK variant are identical to the proteins in the variant targeted by Pfizer-BioNtech mRNA vaccine.

It is important to remember that the way in which this new variant is transmitted is the same as it was before. So, handwashing, mask wearing, and social distancing will help to stem the spread of the virus no matter which variant.